In a series of conversations with women in diverse power sector roles, Utility Dive explores how the current landscape will impact the future.

The country is in the throes of a reckoning in the workforce. Politicians, media stars, executives and journalists have come under fire for alleged misbehavior in the workplace.

In turn that led to social media campaigns, like the #MeToo hashtag, and increasing scrutiny over what constitutes proper behavior in the workplace. But these issues are only part of a larger problem of how companies are defining women’s roles following an influx of women in the workforce a century ago.

The utility sector is no exception. And its problems are urgent: About 70% of the workforce is set to retire in the coming years. Utilities are scrambling to recruit a younger — and more diverse — workforce for an industry known for the opposite.

“The [#MeToo] evolution that is happening now is long overdue,” said Barbara Lockwood, vice president of regulation at Arizona Public Service, the state’s largest utility.

Women composed 22% of the utility workforce compared to 47% nationwide in other industries. This is all despite studies showing women benefit a company’s bottom line. For example, a 2015 report from a Boston-based trading platform, Quantopian, said women CEOs in Fortune 1,000 companies drive three times the returns of S&P; enterprises dominated by men.

“Clearly women at all levels contribute to a higher manner to an organization achieving its high goals,” said Dwain Celistan, an author of a white paper titled Making Diversity Work: Changing times, mindsets and strategies in the technology and professional services industries. “It’s the organization’s willingness to enable women in all levels to reach their capabilities.”

But how can utilities remake the power sector into a space that attracts and nurtures women? This is something Utility Dive explores in a series of conversations with women in the power sector — from the C-Suite to the arduous lineman position.

Recruitment

The first step to identifying promising recruits is knowing where to find them, and then sell them on the company. This is something utilities are keenly aware of as they find themselves competing for recruits against solar and wind companies, which attract millennials.

“One of the things we need to do a better job of in our industry is talk about the meaning and the purpose that we have as an industry,” said Patricia Vincent-Collawn, CEO of PNM Resources and the first female chair of the Edison Electric Institute (EEI), a powerful trade group for investor-owned utilities. “There are a lot of folks getting ready to retire and we need to attract a younger generation and they care about a company that’s doing good things and changing the world.”

In particular, utilities need to craft a more diverse workforce that can reflect the changing demographics in the United States. Women are 50% of the population, but that is often not reflected in many fields, especially the STEM ones. EEI has received a lot of heat over its ongoing “Lexicon Project” that aims to revamp key words and perceptions in the industry. While much of the controversy has focused on rooftop solar battles other parts of the project centered on how utilities market themselves.

According to a power point obtained by the Energy and Policy Institute, a liberal watchdog group, EEI notes that consumers perceive the word utility as “old,” and “monopoly,” which it is in many states.

In light of that, EEI suggests rebranding to “smart,” claiming it speaks to “innovation, efficiency and continuous improvement.” With that in mind, utilities can better target women and millennials; two demographics that would be turned off by stodgy and old industries.

LaTonya King, head of diversity & inclusion for Duke Energy’s human resources department, said that centering the company around the workforce environment is the first step to attracting more diverse pool of applicants.

“It starts with how we even attract them to apply to jobs here,” King told Utility Dive. “The experience going through the hiring and selection [previews] their experience in onboarding.”

Onboarding is key to showing off how the company can nurture talent.

“We go across the whole lifecycle through their entire employee experience,” King said. “Where we have the greatest opportunity [of showing growth] is through the onboarding process, and making them aware of opportunities through our employee resource groups.”

Employee resource groups have become an important tool in companies’ arsenal to help establish growth options to all employees.

These groups provide “opportunities with the company, to network with their peers and to actually serve in leadership roles and really try to connect them to the company,” King said. Other ways to help recruit a diverse array of applicants include training efforts focusing on inclusive leadership and “addressing unconscious bias in our decision-making,” King added.

These efforts often stem from the top down. Duke CEO Lynn Good emphasizes the need for these types of training, King said.

“It’s a journey and it’s a journey for every organization,” King said. “We continue to grow and a lot of our focus is really developing our leaders. And that starts quite frankly at the top of the organization. [Lynn Good] set a great tone around the importance of inclusion and how we lead. That trickles down and cascaded down in terms of messaging.”

But it doesn’t stop at recruiting. Once you find that perfect potential employee, the next hurdle is ensuring they remain with the company.

Retainment

Companies are finding it a challenge to keep top-performers around for a long time. In past generations, benefits such as pensions were incentive enough. But that isn’t the case anymore, and companies are searching for avenues to reel in and keep employees.

Such success largely depends on internal culture. Experts say improving the company’s culture can enhance recruiting — and is vital to keeping female employees. Some ways to improve culture could be through employee resource groups and mentorship programs.

“Those organizations who have embraced women … those women have been able to reach high levels across functional areas,” Celistan said. “But if you are not really an organization that embraces it and all leadership seems to be one gender, and that is male, that organization loses out on that opportunity. Many organizations unwittingly do that. I don’t think the organizations that do that have a strategy but it’s behavioral.”

Usually it traces back to the hiring process, Celistan said.

“As companies look at a pool of candidates, and let’s assume there are diverse candidates of the pool, the questions with which they are asking and the lens through which they are listening to the responses … are sounding more like they want to hear,” Celistan said. “They are sounding more like the existing talent pool that they have, [and] thus you have a reinforcing cycle.”

Experts say companies can break out of that cycle by weaning off employee referrals and engaging women in conversations about workplace culture. A fundamental feature that could help keep women in the company involves flexible work schedules. Some roles don’t allow for that, Celistan noted. But where flexibility can be established, it could encourage women to stay, especially if they take off time to raise children.

“As you look at the workforce, many times women have more responsibilities holistically than the male counterpart,” Celistan said. Those women often choose more flexible roles that could hinder their ability to climb the corporate ladder. Companies that ensure flexibility and growth opportunities e.g. the ability to nurture leadership skills, are more likely to see a diverse workforce.

“The great thing about it is when people see it in action, you don’t have to work as hard to attract women and minorities because they can see it in [your] leadership,” PNM’s Vincent-Collawn said. “Once people see that being a minority or female doesn’t hurt them in their career, they want to come to that company.”

Another key element to retaining an employee is good compensation. The controversial gender wage gap highlights many of these issues, and could be another step toward advancing women in the power sector.

Gender Wage Gap

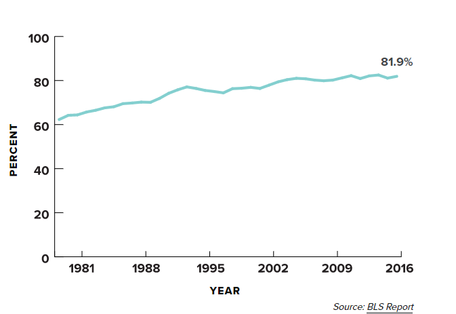

The gender wage gap is usually boiled down to this popular snippet: women earn 77 cents to every male’s dollar. But the Bureau of Labor Statistics reveal a much more complex picture: in some professions, women earn as much as 82 cents to the dollar depending on the profession. Broken down by race, white women earn more than their Latina and African-American counterparts.

The wage gap is more disparate in more technical fields, such as engineering, science and computer sectors. In other fields, not so much. And, starting out, the wage gap is very narrow between two recent college graduates beginning their careers. But as they progress in their respective careers, the gap widens.

Women’s annual average earnings trail men’s

“Generally as you move up, as you move to higher paying positions, gender wage gap gets larger,” said Chandra Childers, senior data scientist with the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. “And a lot of that is that due to segregation — men and women tend to work in different occupations.”

A lot of those occupations are more flexible to a woman’s schedule, especially since studies have shown women are the primary caretakers of the family — direct and extended. Take that societal norm coupled with the fact many women take a few months off should they decide to start a family, and the woman frequently finds herself struggling to play catch up once she returns to the workforce.

“By definition, 15-years out, the male more likely would have 15 years of work and the female may have less than 15 because of potentially having children for example,” Celistan said. “So if they got laid off for a year in that 15-year timespan and that female candidate had a child during that time, she would essentially have fewer years of total work experience. That, unfortunately, is the comparison in years of experience and that does and can play a role for some people.”

Even if women just take a year off, some have difficulty returning to their original roles.

“What they lose is time,” Celistan said. “They lose the momentum of their career … some other women see their life has changed holistically and that they don’t necessarily want to ramp up the same way.” Oftentimes that means women would move down the ladder into roles that pay less, but are more flexible.

But that isn’t true for every case — some of the wage gap stems from the fact women are less likely to negotiate for a higher wage than their male co-workers.

“When women do negotiate, they tend to face more backlash,” Childers said. But more often than not, “women don’t know they are being paid less.”

One way to counter that is wage transparency, something Barbara Lockwood, vice president of policy at major Arizona utility Arizona Public Service advocates for.

“To me, it all goes back to, there is probably is a systemic issue the types of roles and justification that comes along with that,” Lockwood told Utility Dive. “There’s such a lack of transparency … there’s a lot of things we can do to fix that. It does require throwing some elbows.”

Even so, the struggle with the wage gap — and even recruiting and retaining women for the industry — traces back to how women and men are socialized from birth, experts say. Overcoming the negative impact from that socialization takes a lot of conscious thought from utilities — and it could require involvement as deep as middle school.

Looking Ahead

It’s never too late to develop a pipeline of talent. The Department of Energy created a program to craft interest from African-American middle-school girls in the STEM fields during the Obama Administration.

And utilities like Duke Energy and Exelon subsidiary Commonwealth Edison have also partnered up with schools and established programs aimed at middle-school girls about energy.

Take, for instance, ComEd’s Icebox Derby initiative. The program is aimed at middle-school girls to cultivate interest in the STEM fields. And for the utility, it’s one way to start nurturing a potential pipeline of talent years down the road.

“There’s going to be different things that cause attrition [or other companies picking off ComEd’s talent] because other companies that see you have the talent,” said Melissa Washington, ComEd’s vice president of external affairs. “One of the things we’re trying to think about the retention of people is focus on building an inclusive environment of support, particularly to women.”

These programs could resolve some of the issues utilities face to recruit a diverse workforce and, perhaps, modernize its image.

“Some of what we do doesn’t lend itself to [more flexibility and diverse workplace] but we should absolutely do everything we can to provide that different type of culture and work experience,” Lockwood said. “That inherently is going to make it easier.”