On Oct. 25, 2019, Keith Giarman and Martin Pocs hosted DHR’s fifth annual conference addressing talent best practices in private equity-funded companies. This year’s conference convened at the St. Julien Hotel in Boulder, Colorado, where a group of PE leaders addressed a range of topics relevant to the proper assessment of human capital.

Keynote Address: Humans are Remarkably Predictable: Why Aren’t You Using This as a Competitive Advantage?

Presenter: Barry Conchie, Founder & President – Conchie Associates

The day started with a keynote from Barry Conchie, a noted leadership assessment guru who has training in cognitive science and is a former Leadership Scientist at Gallup. He set the stage for the day, exploring key biases we unintentionally embrace when evaluating people.

Key Findings

Mr. Conchie’s thesis was simple: Notwithstanding a plethora of data-driven tools and processes, our track record for selecting the right people is poor, at best. He cited three reasons for our shortcomings in this regard:

- Company leaders spend too much time thinking about profitability rather than strategic growth, in part, because they can’t properly assess probability and risk.

- It’s difficult to overcome our covert biases, our inclination to pick people just like ourselves and our tendency to self-replicate our dominant capabilities.

- Most leadership teams can’t identify and exploit their true strategic imperatives.

A threshold problem to overcoming these issues is that too many top-level executives have an inflated view of their success in picking the right people. Mr. Conchie cited a longitudinal study conducted on the hiring practices of 100 high-level executives:

- When asked to rate themselves on a scale of 1-5 for their ability to hire great leaders, 73% of executives gave themselves the highest possible score, while nobody scored themselves a 1 or a 2.

- While the executives considered 68% of their executive-level hires to be top performers, the reality was that only 12% of them turned out that way.

- Eleven percent of executives claim to hire top performers 100% of the time, whereas research shows 3% pick top-quartile performers just 18% of the time.

We Are Human: We Make Bad Bets

One reason for our deficiencies in making the right hiring choices is that humans are bad at assessing probability, according to Mr. Conchie. Taking the attendees through various exercises, he demonstrated how our tendency, between conflicting options, is to bet the farm on the downside but are relatively conservative on the upside. This can be a fatal error for companies because our inherent aversion to risk on the upside acts as a constraint to growth and, likewise, affects our ability to see upside potential in people.

In identifying candidates, we should be trying to predict the 9-11% of people who are more immune from this constraining influence on risk. The challenge is figuring out how to find people with a propensity to think and operate that way and who are, therefore, more likely to seize upside opportunities for their organizations.

We Don’t Like People We Don’t Like – Even When We Should

Mr. Conchie then took a deep dive into how our biases often override the supposedly objective evaluations we conduct when hiring and evaluating performance.

He discussed an extensive study on bank performance he conducted in which he compared the ratings regional managers gave their branches with the actual performance of those branches. The study revealed a surprising negative correlation between the scores and performance – the branches rated the lowest were, in fact, the highest performers.

Why? The regional managers simply did not like the branch managers at the highest-performing branches. They didn’t like them because of the very reasons behind their success:

- They were demanding;

- They asked tough questions;

- They often defended the customer against their own bank; and

- They had higher expectations for service delivery than their own bank was able to provide.

In sum, the managers based their ratings on likability and ease of management rather than results.

“This wasn’t a performance evaluation; this was American Idol on stilts,” Mr. Conchie concluded.

“If you are a really nice team player and you show up with bright eyes and a bushy tail; if you don’t create any ripples and you’re eager to do whatever your manager wants, you’re a dream to have on the team. As a result, you are going to get a higher rating than the people who are actually performing, but who could not or might not fit that mold.”

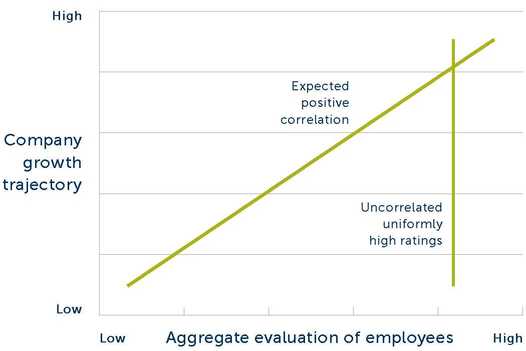

One result of these personal biases in the face of contradictory performance data is that the aggregate evaluation of performance within an organization doesn’t correlate with the growth trajectory of a company. In a study of 73 companies, Mr. Conchie found almost no variation in the overall aggregate score of employee performance; it was 4.1 on a 1-5 scale, regardless of whether the company “was hitting it out of the park or was about to close shop.”

“We’re not suffering from too much objectivity. We’re relying too much on our native wit and judgment on the assumption that humans can apply rational criteria when making refined decisions about performance. We get it systematically wrong time after time after time.”

The Problem with “Cultural Fit”

A related bias problem relates to the amorphous concept of “cultural fit” when evaluating external hires. Mr. Conchie’s concern is that we don’t have a way to define and measure “cultural fit.” Instead, we think of cultural fit in terms of the capacity to get along with our peers at work. When we use that construct as part of our selection process, it often excludes candidates who have characteristics we don’t like, even though those characteristics may be precisely what the individual leader and overall organization needs.

While personality-based tools can help in developing people, they should play no role in the hiring process. Too many companies use them for this process, believing the information helps them make “cultural fit” decisions. They don’t help and they shouldn’t be used for this purpose. Too many companies place disproportionate weighting on characteristics they believe are important – using personality assessments erroneously to justify their decisions – and thus wind up replicating the results they would reach without the use of these tools.

Mr. Conchie conducted a review of 2,681 C-suite candidates, 88% of whom the executives leading the candidate search identified as having a strong cultural fit. Of that 88%, 873 were fired or voluntarily left within three years. Only 7% became top-quartile performers.

“Cultural fit, as a filter, didn’t seem to have the returns that many people use as the reason why they interject it within the selection process. The evidence doesn’t support it very strongly as a construct.”

Bias Against Strategic Thinking

The biases we bring to the selection and evaluation processes also manifest themselves in the choices we make about who to promote internally. The result is a significant problem in terms of strategic thinking at the highest levels of companies.

Mr. Conchie discussed the differing perceptions between operational leaders and strategic leaders regarding the performance and value of their peers. Using 360 assessment data, he found that operational leaders rated strategic leaders much lower than other operational leaders. In fact, operational leaders rate strategic leaders lower than any other category of leader.

But strategic leaders also rate other strategic leaders lower than any other category of leadership.

Part of the reason for these perceptions is that it’s easier to define and quantify operating behaviors; operational leaders get stuff done. In turn, this creates a bias against strategy, the result of which is that organizations tend to weed out strategic thinkers several levels below the leadership level. Conversely, the high value we place on operational leadership leads to individuals with such talents rising through the ranks claiming to be strategic thinkers even though they clearly are not.

The very characteristics that make effective strategists often result in their termination lower in the ranks. They’re also often the same qualities that result in negative performance evaluations, as discussed above. Executives or managers may see a strategic thinker as not playing well with others because they challenge assumptions or the way the company does things. They ask hard questions and are perceived as slowing things down. It is, therefore, no surprise we have a narrowing of the strategic talent pool toward the top of organizations. Companies that complain about their lack of strategic thinking in top executives are oblivious to their organizations weeding out these individuals well before they become visible to upper leadership roles.

How to Overcome Our Biases

Interjecting a credible assessment into a decision-making process will help you get the decision right eight times out of 10. He described the predictive psychometric assessment his company has built and used precisely for this purpose. It is based on the largest C-suite leadership database in the world and comprises 58,000 leaders.

What’s frustrating for us is it means that two out of every 10 people that we say will be top-quartile performers will fail. But that’s still better than the four out of five the very best executives can do on intuition alone.

Mr. Conchie concluded that one of the ways to address bias and to counteract the issues of likability and cultural fit is to challenge perceptions with credible assessments.

“We’re not as rational as we think we are. We’re not gifted with special powers. My advocacy to you is to challenge the presuppositions that you’ve got around the characteristics that you look at when evaluating people and be open to the fact that you might be no better than the data output from an assessment tool.”

Panel 1: Leadership Assessment Tools & Methodologies: Best Practices & Potential Trade-Offs

In a robust and engaging exchange, Keith Giarman, Managing Partner of DHR’s Private Equity Practice, oversaw a panel of four leadership assessment experts who have worked extensively in and with the private equity community. This panel included:

- Tiffany McFerrin, Founder – Solstice Talent

- Julie Wolf, Senior Business Partner, US Business Leader – RHR International

- Nicole Morris, Managing Consultant – Vaya Group

- Ben Holzemer, Partner and Head of Global Talent – TPG

The panel discussed various assessment tools and methods, including their challenges, merits, trade-offs and proper use.

Key Findings of Panel 1

- Context and clear criteria for candidate qualities at the start of the process are essential for the usefulness of any objective assessment tool, as well as for productively debriefing boards, CEOs, and PE partners at the back end of the process.

- Avoid “leading the witness” and telegraphing the answers you’re looking for in interviews.

- PE-funded companies’ increased use of objective assessment tools is a positive development, but the proliferation of proprietary assessment tools by search firms can create inconsistencies and confusion among clients.

- A wide array of inputs is necessary to overcome the challenges of assessing emotional intelligence.

Context is Indispensable

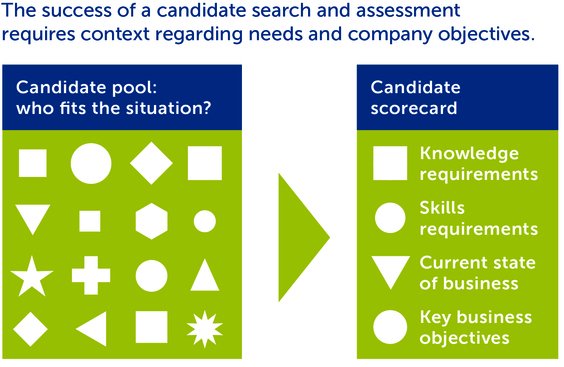

The discussion began with the panelists emphasizing the importance of context when using assessment tools. For a candidate search and assessment to be productive, you must provide context around what you’re looking for, the state of affairs inside the business and / or department and the key business objectives associated with the role. Without clear anchors like a scorecard or success profile informing a contextual understanding of search criteria, you can use any test in the world, but you won’t know what you’re trying to derive from those assessments.

The panel discussed the benefits of objective assessments, including using a mix of personality or working style inventories, such as Hogan assessments, along with cognitive ability assessments like the Watson Glaser critical thinking test.

The literature suggests that cognitive ability testing, such as the Watson Glaser critical thinking test, is a great predictor of performance in high-level roles that require dealing with complexities, higher levels of critical thinking and reasoning abilities. If a candidate performs below a certain level, it may not necessarily disqualify that individual as other data sources and additional probing may be able to provide context for the candidate’s reasoning.

Context is also critical for debriefing and advising boards, CEOs and the human capital partner on the back end of the process. This includes developing a clear understanding of the PE sponsor’s investment thesis, business imperatives and role imperatives. That allows for a beneficial discussion that goes beyond describing how a candidate thinks or operates to discussing how the person’s qualities align with the company’s priorities and objectives.

“No candidate is perfect and doing a rigorous candidate assessment – including psychometric testing – is a risk-mitigation tactic. Having context helps companies mitigate the risk that the candidate will not be able to deliver what is most critical to success. For instance, an organization may already have a vision and go-to-market strategy in place, but what they really need is a CEO to come in and energize the management team around this vision and implement it flawlessly. Without this context, you may find yourself with an incredibly visionary CEO candidate who lacks the execution and influence skills necessary for this particular situation. Context is the target you are shooting at.” – Nicole Morris, Managing Consultant – Vaya Group

Avoid Leading the Witness

Concerning behavioral interviews, the key is to avoid questions that telegraph the answers you’re looking for. Asking curious, open-ended questions results in a cleaner dataset rather than a dataset that flows from leading the witness. Ask fewer topic-level questions but dig further into how and why specific episodes in a candidate’s career transpired the way they did. Learn why the candidate approached a situation in a certain way versus another.

- What was the situation?

- How did the candidate analyze and determine an appropriate diagnosis to resolve?

- What did the candidate do with whom, how and why across what timeline?

More specifically, carefully drill into specific examples of situations the candidate encountered and successfully resolved, with an emphasis on metrics, people, systems, and process improvements. Importantly, ensure that the candidate’s answers show evidence of a hands-on approach to problem-solving working with their teams. Highlight lack of clarity on the part of the candidate and use other interviewers to probe uncertain responses.

“The most reliable data comes from what actually happened in past situations, not a candidate’s aspirational approach. When you hear a candidate say, ‘What I like to do is …,’ steer them away from hypotheticals and back to what they did in that particular instance. It’s also helpful to ask a balance of where their actions were successful, and what they might do differently going forward even if the outcome was good. The best candidates can self-critique objectively.” – Tiffany McFerrin, Founder – Solstice Talent

Wide Array of Assessment Tools Can Create Inconsistencies

The panel noted and approved of private equity-funded companies’ increased use of objective assessment tools. But the group also expressed concerns about the proliferation of assessment approaches, specifically those of search firms that create and implement their own proprietary competency matrices, scoring rubrics and psychometrics. Such inconsistencies in methodology, scoring, numbering schemes and other elements can be confusing.

“It feels like the early days of computing where we need a common operating system. If we can get a number of the major search firms and assessment and leadership advisory firms to align consistently around a few tools, it’s going to make it a lot easier for big clients to understand what the data means and actually track it over time.” – Ben Holzemer, Partner and Head of Global Talent – TPG

“HR and talent management are often maligned for not driving demonstrable value for the enterprise. However, by leveraging executive assessment, they can have a huge impact on the bottom line by reducing poor hiring decisions and saving their organizations millions of dollars.” Julie Wolf, Ph.D., Senior Partner, US Business Leader – RHR International LLP

You Need a Constellation of Inputs to Assess Emotional Intelligence Effectively

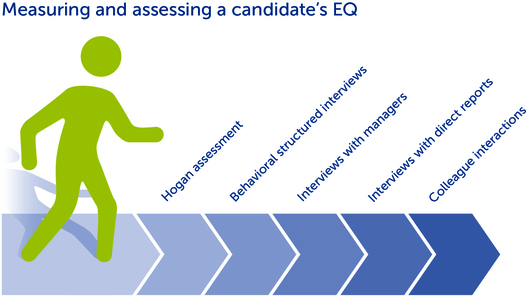

Even though we can discern certain aspects of emotional intelligence through tools like Hogan and other elements like self-awareness through behavioral structured interviews, measuring and assessing a candidate’s EQ and, specifically, the candidate’s ability to empathize is significantly more difficult. It’s hard to definitively say whether a candidate has it because there are so many definitions and ways that people measure it. You need a constellation of inputs to get keen insights into things like transparency, integrity, empathy and humility, with an eye toward understanding the level of self-awareness of the individual being considered for a specific role.

“Empathy is an effective response that stems from the apprehension or comprehension of another’s emotional state or condition and is similar to what the other person is feeling or would be expected to feel in the given situation.” Eisenberg 2005

This can include interviewing a candidate’s managers, direct reports and colleagues to assess how well the candidate has demonstrated the competencies required for the position in previous jobs and to identify the candidate’s leadership and functional work styles. Encourage board members and the deal partners making the hiring decision to make some of those calls, listen carefully and home in on those issues. In sum, the goal is to discern what this person is like to work with every day. Additionally, try to move beyond all the formality of the interview process and push for some social time with the candidate, as challenging as that can be logistically.

Panel 2: The Quest for the Perfect Leader: Real-World Trade-Offs Required to Realize Optimum Fit

The day ended with a session moderated by Jeff Cohn, with support from Keith Giarman, discussing research on the top leadership attributes of successful CEOs as identified by PE partners around the country. In an interactive discussion, Jeff and Keith introduced a “mock” search with three finalist candidates. The audience helped decide which CEO candidate would be the most suitable to hire in a $200 million home health care company.

Key Questions Addressed

To ensure proper “fit” across several dimensions, how important is:

- Prior experience that maps to the situation at hand, including the scale of the company, growth or transformation plans, etc.?

- The fact that an executive drove value and realized a recent and successful exit working in a private equity context?

- Specific domain experience with respect to a product, market or industry, or highly technical competencies that suggest better product and market fit?

- Building a motivated, accountable and highly engaged management team that embraces the company’s mission and plans for financial and strategic success?

The Three Candidates

The panel began its mock hiring exercise by presenting the three candidates who made the final cut in the hypothetical home health care company’s search for a new CEO:

Candidate A: This individual spent two years as a sales executive and was CEO of various businesses, including a Fortune 20 company. She has a history of alcohol abuse, which she seems to have overcome. The candidate is very good at hiring top talent, has a metric-driven approach and holds teams accountable. Notably, the candidate has no health care background or experience.

Candidate B: While this candidate has no CEO experience and has never built her own team, she has very deep industry experience and a consistent track record of success.

Candidate C: A seasoned CEO with solid health care industry experience, this candidate has had mixed results and tends to go slowly according to some references, who also question the candidate’s self-awareness.

Key Qualities PE Firms Seek

Using these three candidates as examples, the panel discussed its findings from surveys of PE executives regarding the qualities they believe are most important in a CEO. At the top of the list were:

- Ability to build an “A-level” executive team

- Integrity

- Resilience and the ability to come back from failure

- Authenticity and vulnerability

At the bottom of the list were:

- Empathy

- Relevant industry experience

Noting that empathy is a crucial characteristic for success as a CEO, yet on the bottom of the list of what PE executives look for, the panel said the problem with empathy in a PE context is that it could bleed into compassion. In turn, compassion can slow difficult decision-making, such as cutting staff. The discussion that followed underscored the various definitions of “empathy” and revealed some confusion about its importance as a key attribute of high-impact leaders, depending on an individual’s definition. For those who understood empathy as personal self-awareness and sensitivity that results in an understanding of how one’s managerial actions affect others – “walking in their shoes” so to speak – it was clear that empathy is critical to effective management and creates “followership” in an organization.

The discussion turned to the critical role of authenticity and vulnerability in a CEO or other leadership role. These qualities are important because the rest of the team needs a safe environment where people are free to take risks and are actually encouraged to do so. Employees need to know that if they make mistakes, they will be coached to help them understand key issues, and work through problems and shortcomings as part of personal and professional development. Some on the panel expressed the view that vulnerability is overrated, while others emphasized that, while a key trait, it should not come at the expense of self-confidence. Do the best leaders have a unique combination of self-confidence, coupled with a more open way, where vulnerability can be expressed? The panel exchanged views as to the importance (or unimportance) of industry experience. How much to weight such experience can depend on a candidate’s agility and learning ability, expectations regarding the investment horizon and how quickly things need to move, and the holistic consideration of the candidate’s other characteristics. There seemed to be a preference for executives that had more industry experience in situations where the company had been held for a number of years and the PE sponsors were driving toward an exit. In these situations, these executives would have less time to learn the nuances of the company and its challenges and, therefore, more industry experience would be preferred.

PE executives see integrity as essential because they need someone who has the courage to deliver the bad news, to share negative information with the board, to be realistic about goals, and to identify roadblocks, as well as plan for overcoming them. In this context, personal integrity essentially translated to a number of other attractive qualities that suggest trust and transparency.

The panel and the surveyed PE executives considered resilience and self-awareness to be significant. Specifically, they valued a candidate’s ability to reflect on failures or mistakes, understand the reasons behind those failures and implement solutions to correct the situation. This notion was reinforced in the prior panel on leadership assessment, where several panelists emphasized the importance of observing self-awareness that led to significant learning in prior roles during a structured interview process.

Finally, the panel agreed the ability to build an “A-team” is the best predictor of CEO success. While roadblocks, such as limited resources for compensation, may stand in the way of hiring all “A” players, an “A-Team” is not necessarily composed of all “A” players – you can’t have a team on which everyone is Michael Jordan. An “A-team” is one that makes the most of a situation and includes the right people and the right talent available under the circumstances.

Given the general consensus on the last point, the majority of attendees picked Candidate A – very good at hiring top talent but no industry experience – as the one most likely to be successful in the health care CEO role, regardless of the candidate’s struggles with alcohol addiction. The panelists wholeheartedly agreed.

The panel concluded by emphasizing the importance of soft skills – vulnerability, authenticity, integrity and empathy – as predictors of success. These are the building blocks for delivering performance and building a team that helps implement the CEO’s strategy. They help you bounce back when you hit a wall and are critical to overcoming inevitable challenges.